Joint Accountability for Behavioral Health Includes You

November 2, 2021 · Andy Reynolds

A three-layer model of behavioral healthcare has strengths that can be built on by people who get, provide and pay for care, a recent report and webinar show.

In the report, Applying the Behavioral Health Quality Framework: How Joint Accountability Can Improve Care, NCQA researchers Serene Olin and Lauren Niles assess the Applegate Alignment Framework—also called the Applegate Model after its creator, Ohio Medicaid Medical Director, Dr. Mary Applegate.

During an October 8 webinar, Serene, Dr. Applegate and four other guests discussed the report and how to improve behavioral healthcare.

Why Behavioral Health Matters

Peggy O’Kane, NCQA President, opened the webinar by saying why behavioral healthcare is a quality priority:

- The pandemic has revealed—and worsened—a mental health crisis and a shortage of services to meet demand.

- Technology is increasingly important to quality and plays a growing role in behavioral healthcare, especially with the rise of telemedicine.

- Behavioral health care is hard to measure. That’s mainly because attribution is complicated. It’s not easy to build measures that account for all the providers and services crucial to behavioral health.

Serene framed the importance of behavioral health in economic terms:

- People with behavioral health conditions account for over half of health care costs.

- Behavioral healthcare accounts for only 4% of health care services.

New Knowledge

Serene explained NCQA’s recent research into:

- What gets measured in behavioral health.

- The impact of that measurement.

Twenty-one interviews of diverse stakeholders across 5 states revealed:

- Myriad measures in use.

- Reliance on nonstandard measures.

- Few measures of integrated behavioral healthcare.

Our researchers discovered consensus among interviewees that:

- Many measures in use are narrow and don’t help improve care.

- It’s not clear who is accountable for behavioral healthcare or how to improve

- Current measurement is burdensome and requires large-scale solutions and incentives to overcome.

The Applegate Alignment Framework

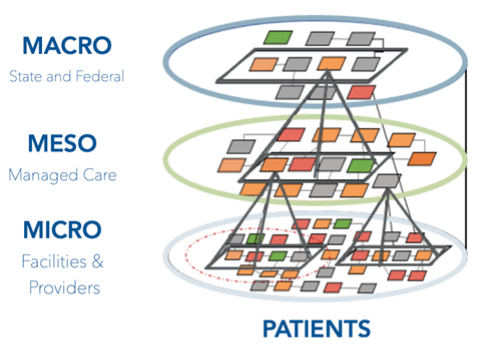

The Applegate Alignment Framework is a population health model that clusters related quality measures at three levels to address population health needs:

The Applegate Alignment Framework is a population health model that clusters related quality measures at three levels to address population health needs:

- The Macro level comprises state and federal regulators overseeing population health.

- The Meso (or middle) level represents organizations that oversee care delivery by providers. This level includes ACOs and managed care plans. Organizations at this level respond to regulatory demands from above and consumer needs from below.

- The Micro level represents people and organizations on the front lines, delivering care.

The point of the framework is to focus reporting on what matters at each level. Measures are “nested” and consistent between levels, and data flows freely between levels.

The State Medicaid View

Dr. Applegate offered valuable context for why a layered model of behavioral healthcare helps regulators:

- Behavioral healthcare costs drive overall costs; almost half of Ohio Medicaid enrollees have a behavioral diagnosis.

- State Medicaid directors have the authority to require coordination and collaboration across systems in their states, such as between managed care organizations and managed behavioral healthcare providers.

- The three-layer model is a way for people across the state to team up and build nested “measure bundles” that meet each level’s quality and reporting needs.

Managed Care: A Payer’s View

Dr. Rhonda Robinson-Beale, SVP and Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Mental Health Services at United Health Group in Idaho, emphasized that “Meso” payers prize:

- Robinson Beale defined attribution as “once you touch a patient, they’re in your denominator and you are responsible for the outcome.” She distinguished between two kinds of attribution: active, which exists in narrow networks, and passive, which exists in more flexible networks and holds providers accountable for everyone they serve.

- Getting data quickly is key. The shortest feasible lag for claims data is one month. Using patient encounter data and information collected when providers check insurance eligibility can improve transparency.

- At least 40% of a provider’s population needs to fit a denominator in order for a measure to reach critical mass and get the attention it needs to improve care.

- “Money up front” drives improvement better than receiving payment a year or more after delivery of care.

The MBHO Perspective

Dr. Gail Edelsohn, Senior Medical Director of Community Care Behavioral Health in Pennsylvania, summarized the view of managed behavioral healthcare organizations by noting:

- Geographic granularity. County-level data are crucial dots to connect in reporting. Stratifying data geographically matters, just like stratifying by race and ethnicity matters.

- Inconsistency and disagreement. The behavioral health framework can help standardize and streamline inconsistent measures, but organizations disagree about whether some of the most common measures are worthwhile. Someone (like NCQA) or something (like a modified quality framework) could help build consensus.

The Provider Experience

Social worker Tammy Allan, Behavioral Health Director for Hill Country Health and Wellness in California, emphasized three facts from the front lines of care:

- Nonstandardized one-offs. Allan confirmed Serene’s report that the volume of unique, unaligned measures is frustrating. Providers don’t think such measures are useful.

- Disparate funding = Complex reporting. Federally Qualified Health Centers rely on different funding streams. Each funder has its own reporting requirements. “This becomes absurdly complicated, burdensome and stymies innovation and quality,” Allan said.

- Training and infrastructure. Integrated behavioral healthcare and social determinants of health are new ideas in many places. Providers need training on those topics. Allan also called for investments to upgrade EHRs so computer systems integrate behavioral health and social determinants.

Consumer Input & Buy-In

Bri Masselli, Division Manager of Mental Health and Treatment in the Office of Behavioral Health for the State of Maine, used her personal and professional experience to relay the consumer perspective.

She urged the 1,100 webinar attendees watching live to remember:

- Engagement. Effective behavioral healthcare depends on getting buy-in from the people whom providers are trying to help. And that buy-in depends on professionals acknowledging the trauma that a patient has experienced. It also means provider and patient acknowledgment that a behavioral health diagnosis deserves attention.

- The right kind of access. Getting someone to commit to therapy may hinge on making early visits easy. The less paperwork and red tape, the better. Helping patients at key times is important, too, such as when they’re moving from foster care into adult care. So does locating care centers where patients already go, such as community recreation centers.

- Involving patients in the process. Asking patients what matters to them is important. For example, young adults are more likely to be honest and open to collaborating with therapists who defer to them on care goals and ask them questions using everyday language.

Masselli’s emphasis on including patients in their behavioral healthcare—which all speakers agreed is vital—was an apt place to end the webinar.

NCQA is grateful to the California Health Care Foundation for sponsoring this important and rewarding research.